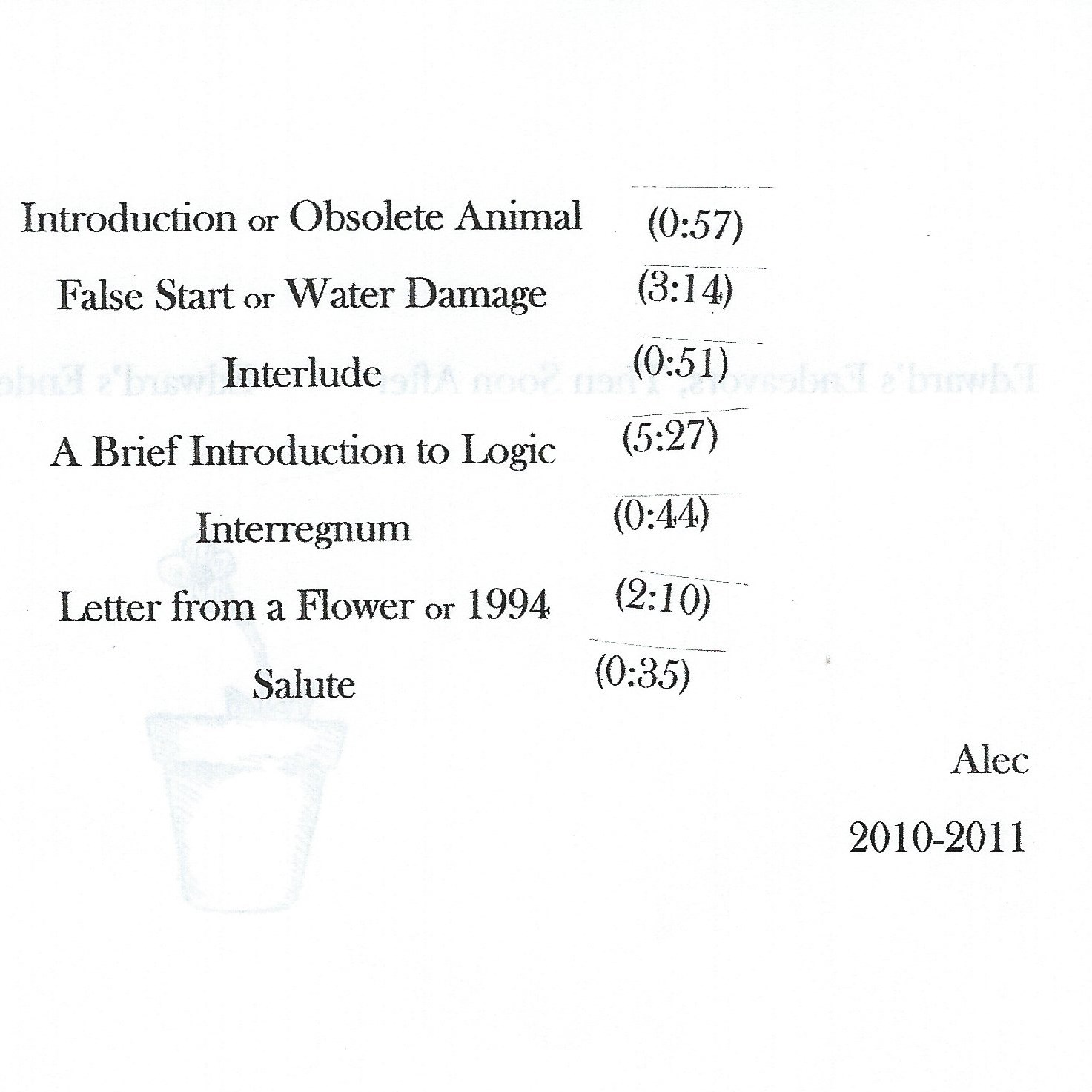

Original track off upcoming album "Carried by Cold Water," hopefully out by fall. More to come soon. Cold River, Wide River The river's cold and the river's wide, We were not prepared. You heard my calls from the other side, Hung in crystal air. Though I know beyond this snow, There is a Spring.

Edward's Endeavors, Then Soon After

Cold River, Wide River/Winds of the West

Cold River, Wide River

The river's cold and the river's wide,

We were not prepared.

You heard my calls from the other side,

Hung in crystal air.

Though I know beyond this snow,

There is a Spring.

Though I know the winds will blow,

beneath your wing,

And carry you away.

The snow came late but the snow came hard,

And the whole town's off-guard,

And April was just the image on,

Generic greeting cards.

Though I know the night will slow,

I can't find my strength.

Though I know the sun will show,

I can't face my pain.

I'm standing at the banks,

Ready to jump I think,

But I carry so much weight,

That I know for sure I'd sink,

Without you to carry me.

Winds of the West

If you're still there,

Why do I still feel alone?

In my rear view mirror,

I watch my eyes turn to stone.

Dirty headlights,

Pave the road I go,

My exhaust pipe,

Breathes a heavy load.

And I can't sleep,

Yeah there are some things only bloodshot eyes can see,

And I left the Midwest,

For a moment I was free.

Drove right through my hometown,

Inhaled 100,000 walking rainclouds.

You'll hear from me when I feel like being tied down,

The winds of the West are calling me.

The winds of the West are calling me.

Carried by Cold Water

Loss Lullaby

What did you say to me that one day,

We were rained on by trees in the Fall?

You would not let me run away,

No I would always be home.

Porcelain skin that shone summer again,

Even through the Winter’s cold,

And eyes that gleamed green in the darkest evening,

And as the nights were growing old.

Yes eyes that gleamed green in the darkest evening,

And as I watched them fade down the road.

As I watched them fade down the road.

-

Winds of the West

If you’re still there,

Why do I still feel alone?

In my rearview mirror,

I watch my eyes turn to stone.

Dirty headlights pave the road I go,

My exhaust pipe breathes a heavy load.

And I can’t sleep,

There are some things only bloodshot eyes can see.

I left the Midwest,

For a moment I was free.

Drove right through my hometown,

inhaled a hundred thousand walking rainclouds.

You’ll hear from me when I feel like being tied down.

The winds of the West are calling me.

The winds of the West are calling me.

-

The Dam Broke Today

The dam broke today,

And the waves carried you away,

To a far, unmarked town.

As the sea swallowed the trees,

You turned and looked at me,

And said “I’m gonna let go now.”

You fell down and shivered,

Our seashore town is just a river.

Oh I’ve got no one now.

So I built a boat,

And set sail on the water road,

And left the town to drown.

But no map would tell the truth,

So I just stood and screamed for you,

But I never heard a sound.

The Sun fell down and shivered.

Reflections fail on the river.

Oh I’ve got no one now.

Oh I’ve got no one now.

-

Let Summer Come

I woke up in November,

An early death blew through my hair.

The last thing I remember,

Was whispering into your ear,

“Let Summer come,

Because this cold, dead freeze is killing me.

Got to escape this city,

It’s drowning.”

I held my breath, I played, I prayed, I paid my share.

The Sun fell through the clouds like,

The strands of your blonde hair,

Well I might be lost.

What am I doing here?

I stretch out my arms,

To let down your hair,

“Summer’s here.”

I lost my timepiece in the Rocky Mountain breeze,

I never know which way I’m going.

And I’m more lost than,

A fly in your mother’s kitchen,

But I know I’m here.

Yeah, I know I’m here.

When the fog declines,

And hides my lonesome way,

I hope you know which way I’m going.

Am I a poltergeist that haunts your memory?

Cause you’re haunting mine.

Yeah you’re haunting mine.

-

Late, Tired Whisper Song

My ghost,

Watches my body decompose,

And bleed out into this microphone,

And my soul,

Well I left it down this road,

In a small town a little closer to home.

Oh you’re wrong,

I’m so far from standing strong,

But the winds I trust to push me on.

Cause I’ve had enough,

Got to stop letting go of love,

And hold on,

Before I just drift off.

Cause you’re not strong,

You’re not strong for giving up,

Oh common,

She is what you want.

Well Love, it haunts.

And happiness, it taunts.

And I’m busy,

Chasing what they flaunt.

I lost,

The first bet I placed on you,

Kept tossing quarters,

Trying to win back what I threw.

Now wishing well,

Ripples stretch through crystal blue,

Shake the oceans,

And storms I’m sailing through.

The winds roar,

I reach out for the shore,

Emptied my pockets,

But I still needed more,

Oh I still needed more.

-

Come All Ye Kings

Come all ye kings in your garnish and gowns,

Come all ye kings in your jewels and crowns,

Rise from the warmth of the cribs where you lay,

That sit up on top of the worlds that you made.

Cause I've seen your battles, your crusades, your wars,

I've seen you force people to wielding your swords,

I've seen your men still and prepared for defeat,

They're laying their rifles down at their feet.

I've seen you build ships for yourselves in the flood,

I've seen you eat bone and drink innocent blood,

I've seen you kneel down and pretending to prey,

Then when we drown you're turning the other way.

Your killers, your thieves, your opponents, your jailed,

Your merchants and serfs, your peasants, your failed,

Your own mothers and fathers and daughters and sons,

You're outnumbered a million to one.

Come all ye kings that fear near and far,

That hide in the shadows- we know where you are,

We march with the veil of the deepest dark night,

To be at your gate in the pale morning light.

-

Swales

Can you see your brothers and sisters cry?

Things have changed, sure,

But then now so have I.

How much longer until their tears can dry,

Or will you let them die with swales ‘neath their eyes?

She said she needed to fly like the eagle soars,

Long blonde hair falling down onto the floor.

For the ailment of sadness I’m told that love is the cure.

That I once did believe,

But now I am no longer sure.

An empty soul will search for more,

And a wild heart will run for sure.

How much longer until my tears can dry?

Or will you let me die with swales ‘neath my eye?

-

Warmer Skies

As the birds flew down,

To the warmth of the South,

You migrated to a town,

Where the Sun takes longer to go down.

Why do you leave so indifferently?

Society,

Let go of me,

Let me fly free.

Cause I need to go,

To a place where,

The Sun will always show.

Trees stand silent with,

No birds to sing,

As I wait for,

Your return next spring.

Why do you leave so indifferently?

-

Where the Winds Meet

Well does it really take a well-trained eye?

She threw a lasso around your neck,

And a noose ‘round mine.

Can you settle the score?

You brought a single rose,

To the one I was waiting for.

Chivalry is dead and I can’t stand it,

But I can’t stand at all.

I got lost somewhere and can’t find my way,

To the place I was.

But it was you who told me through a wooden door,

When I was just a boy getting dressed,

That I must un-tie the mast and set my sail,

And the wind would do the rest.

But look where that got me,

Just stranded where the winds meet.

And can you settle the score?

You brought a single rose,

To the one I was waiting for.

-

Cold River, Wide River

The river’s cold and the river’s wide,

And we were not prepared.

You heard my calls from the other side,

Hung in crystal air.

And though I know beyond this snow,

There is a Spring.

And though I know the winds will blow,

Beneath your wing,

And carry you away.

The snow came late but the snow came hard,

And the whole town’s off-guard,

And April was just the image on,

Generic greeting cards.

And though I know the night will slow,

I can’t find my strength.

And though I know the Sun will show,

I can’t face my pain.

I’m standing at the banks,

Ready to jump I think,

But I carry so much weight,

That I know for sure I’d sink,

Without you to carry me.

-

Down the River

When you come,

When you come looking for me,

Down the river’s where I’ll be.

Down the river you’ll find a lady,

Eyes of pearl and tears of stone,

Arms like vine and thighs of Poison Ivy,

And I can’t have her, no.

Now I,

I just need to go.

When she comes,

When she comes asking for me,

Down the river’s where I’ll be.

Down the river the last standing tree,

Bends down sickly and low,

The winds blow tears of leaves al down beneath,

The sadness of my mother uncontrolled,

Now I,

I just need to go.

When my mother comes calling for me,

Down the river’s where I’ll be.

Down the river is one watchful King.

He sits on hills of soulless gold.

Always caught in a tight periphery,

He’s lost his place in tales of old lore.

Now I,

I just need to go.

When he comes,

When he comes scouring for me,

Down the river’s where I’ll be.

Down the river his heavy army,

Melts the past and digests the road.

Heads of rust and hearts of gasoline,

The breath weighs heavy with the common cold.

Now I,

I just need to go.

When they come,

When they start coming for me,

Down the river’s where I’ll be.

Down the river a wild coyote,

Howls among the stars, dark skies of coal.

To the hills he runs on with a warning:

“I’ll tell you once then I’ll say ‘you were told.’

Now I,

I just need to go.”

When you come,

When you come following me,

Down the river’s where I’ll be.

Down the river time’s lost poetry,

Piles among the mud, the trail ran cold,

And one day soon you’ll wander right into me,

Shriveled and defeated, hung down and old.

Now I,

I just need to go.

-

Now I’m Gone

Here they leave a wild soul to wander,

Yellow seas will rock him in his sleep.

Here they leave a wild prize to squander,

An ease to touch, impossible to keep.

Now I’m gone,

Now I’m going home.

Here they leave a quiet land to conquer,

Narrow skies, arms are reaching wide.

Here they leave a stainless crown to launder,

Yell the crows, weeps the untamed eye.

Now I’m gone,

Now I’m going home.

-

There He Went

There He Went

Alec James

There he went. The Interstate lain bent over the curved surface of the Earth. To the mountains laying some distance ahead, we all assumed, he must have been headed when his rustic red ’72 pickup truck suffered a severed fuel line. Spotted chrome wrapped around large fish-eye headlights that always seemed to hold an intense attentive vigil on the road ahead. They spread into thick white stripes stretching to the back bed door, a couple large holes poked through the thinning medal during times he misjudged how fast he was flying down dirt roads and slid into a tree or metal fencing. I remember him giving me rides all the time in high school. I remember him cursing at the lock, telling me that the doors, they have trouble opening sometimes. You could see where three decades had taken bites out of the body; rust had spread out like the wings of an eagle from every crevice and crack. However beneath rested the sleeping shreds of bright red warrior paint, and one could see the fierceness it once had back in its youthful days when his father would get sick of wherever he was and take the same truck from one coast to the other. When he finally showed up a few months later, he “always had this look on his face, like he was expecting some kind of welcome-back party,” according to Johnny’s mother.

I guess he wanted to be invisible again, leaving at such a late and dark hour of the night. He wanted to do what his father did a hundred times before. He wanted to be there one day, and be gone the next. The Milky Way split the pitch black sky in half as gasoline quickly began to shower every little outdated piece with a flammable rain. The desire for invisibility is a little ironic, concerning that minutes later the boy and the old truck were both a giant fireball rolling over the dark abysmal horizon. It took fifteen minutes for someone to drive by and notice, another ten for the fire trucks to arrive, and five to pry the coal-colored carcass of Johnny Karwin out from the entrails of the steaming aluminum skeleton of the truck he swore would never die on him. I assume that even in the deepest reaches of space, stars always burn out strong.

He was just nearing the age where his life in the sun was beginning to form subtle spots on his skin, though still as smooth as it was the day he was born, says his mother. His hair was the same shade as the mud after a hard rain, and it stuck back and out into askance tuffs, one stretching toward every city in the country. When he was a boy, you could see his rebellion flowing down to his shoulder blades. Every teacher he ever had and each of his accidental acquaintances in the town would beg him to “please cut that hair of yours.” Both he and his father refused. He probably hadn’t seen his own chin in half a decade either. Ever since his facial hair started coming in years ago, he let it stick out everywhere just like the hair on his head. You would see him around town with a cigarette hanging out of his mouth, looking like Tom Sawyer probably did after he grew up and became a criminal. Of course, I didn’t know his father well, but some of the older folks in the town say he was just like him and I believe it. That kind of potency just has to be biological. When people like that disappear one day, you never know why.

I was at the Karwin house the next day with his mother and a few of the people appointed to the task of making the news official. I was sitting at an old wooden table across from Johnny’s mother. You could tell, from the spots in her face which had grown tired of gravity and sunlight, that she was not young. The skin slid along her skull like the contour lines on a topical map, bearing an ashen yellow which seemed to stir thoughts of the antiquated pages from leather-bound books belonging to another time. From these overt facts, one could say that perhaps she was nearing the age of sixty. However the very face which claimed to be so aged seemed to gleam with a vitality one would expect from adolescence and not an instant past, almost as if she were constantly laughing in the face of time, or aging, or degeneration, or the forward pressing of any change at all. This fervor gave a glow to old pages and dimension to maps, making the very act of estimating an age seem like a formidable task. She was sitting in a dining chair, with a posture straight out of an artist’s sketchbook. Legs crossed, back bent with a rolled spine bending her torso forward. Her left arm was draped over her right knee, and while looking relaxed, still seemed to stretch out toward an unseen gravity beyond the house walls before falling at the wrist to form her hand and fingers. Her right elbow was perched against her upper thigh and waist, moving the cigarette in her hand up to her mouth and back down again, as if controlled by slow internal clock gears. Her pupils fell to the lower left, holding a sad contemplation. Each time her hand rose for a drag, her eyelids would squeeze and press inward toward her brain in a squint. She always looked like she was experimenting with jigsaws in her mind, trying two particularly suspicious pieces together here or there, making mental masterpieces from pencil strokes.

The details started to come. Slowly, and one at a time.

“Cars don’t necessarily explode,” the technician said to the investigator, who was staring intently as if the words spoken were being physically excreted from the mouth and deserved special analysis. It tortured me. I’ve had dreams of his skin melting off of his skull. I heard him scream as he drowned in the boiling oceans of hell. I saw his skin blistering and popping into corpuscular craters, and his lungs filling up with smoke as he shook in bereavement of air, heaving into asphyxiation. I could see his frantic eyes widening, as round as his truck’s headlights, as his arms violently jerked the driver side door over and over, cursing at the lock.

“In technical terms, an explosion would require gas being compressed in some form of container. The cabin of a vehicle is much too large for the amount of gas, so really, cars just burn immensely.”

I kept coming in and going out of the conversations. Ringing throughout my ear canals were the words of the investigator: “Severed fuel lines? Yeah, they can happen naturally, but only rarely. We just want to explore all possibilities.” And I kept seeing the flame-red veins desperately crawling toward Johnny’s constricting pupils. I saw him screaming. Fucking lock. Goddamn fucking lock.

“Nothing is really a rarity in a neglected truck made in the early seventies.”

I could feel my eyes flickering back and forth, from his mother to the technician, to the investigator to the television, where muted home videos were being played. His mother was watching them since she got the news early that morning. The image would go in and out of focus, and there would be long instances where poor tracking overtook the screen with bands of static snow. It reminded me of the winter a couple months prior, when Johnny and I were on a late drive.

It was one of those incurable diners. The kind where the bathroom floors were so profane with stale urine that your shoes stuck and seemed to sink, ripping away from the tile, each step following through with the sound of separating Velcro. It was the kind where the urinals were never flushed, and the faucets were always left dripping. When the snow became so dense and churlish that even Johnny surrendered with the confession that he had to pull over, the only light in sight was the florescent-bulb twinkling shining through the diner’s cataract windows.

“Take a seat wherever you like.” His eyes were plagued purple with insomnia and his skin was pale and splotchy from enduring the winter thus far. He was tall and skinny, with arms so disproportionally long that his silhouette could easily be confused for a young tree had he been reaching for the stars. We glanced around the small dining room, populated only with microbes, and I followed Johnny to the corner booth.

“Shit, it’s three in the morning,” mumbled Johnny, glancing at an analog clock sitting in the kitchen window. In my periphery, I could see the tired waiter awkwardly moving his limbs over to the edge of our table and placing two glasses of water on each outward corner.

“What else were you two wanting to drink?” He was probably in his mid-20’s, although his skin looked aged and yellowed, like when your chain-smoking mother takes down a picture from the wall for the first time in twenty years and you can see where the tar set into the wallpaper and paint. The entire house was addicted to nicotine.

“Uh, first, where are we?” Johnny always had a way of talking which sounded skeptical regardless of the situation.

“Oh, this is a bad storm to be lost in. Where are you from?”

“Georgia.” We are from Missouri. Johnny showed up at my house and said “hey, I’m getting out of here.” He did this occasionally. Something would irritate him, what exactly it was, there was no telling, and he would drive all night and only turn back when he started to see the sunrise. He would say that he just wanted to be somewhere else when the sun came up again, somewhere in which the horizon was hiding from him at sunset. It was a new day, a constant reminder that time is invariably moving. As time moved, so did he. “Otherwise,” he would say, “how would you ever know?” He wouldn’t ever tell me this, but I could tell that beyond the impulse, the hidden design was always to never turn back. A new day, a new place. A new place, a new life. When you become lost, every direction becomes equal. The moment the sun comes up, that is the moment to decide- to go back or to go forward. He called these “dark departures.”

The waiter chuckled. He looked dead. His skin clung to his skeleton like an old dress hangs from a secondhand store hanger. “Well, I’m not sure how you found your way into Kentucky. Especially in a small town like this.”

“We’re not going back to Georgia. We’re running from Georgia.” Wherever he went, Johnny always spoke straight through people. If that makes sense. “Are there any forests around here?”

“Oh, I wouldn’t know. I have barely ever been out of town in my life.”

“Gas Station?”

“Down the road, but it doesn’t open until around seven.”

“Gotcha. I’ll take coffee.”

The waiter shifted over behind the kitchen and out of sight.

“My God,” said Johnny, “I can barely accept the fact that I have to stay in this world my entire life, and this guy’s completely content with being a single bacterial cell in this microscope slide of a town.” He went on to say that all being stagnant did was attract mosquitoes, and people who just stick around are the reason why nothing changes anymore. “1984, George Orwell said that the reason oppressed people don’t fight back is because they don’t have anything outside to compare their current state to anyone else’s. Uncle Sam learned his lesson in the sixties- once you make it to the top, the last thing you want is a counterculture to take root and potentially upset the structure you just climbed.” He looked around as if whispering away from an imaginary eavesdropper. “That kind of deception is too profitable to change. Now Uncle Sam is yelling ‘don’t leave and see the world, we are all the world you need to see!’” Inflicting that kind of attitude, he said, is meant to keep us static and to keep outward comparison limited so the fat pigs could continue feasting on the masses.

“1986, the U.S. bombing of Libya, remember?” He looked at me with determined eyes. I nodded. “Guess what time the bombings started.” I looked at him blankly for a few seconds. I didn’t know. “Exactly at seven in the evening, eastern time. Guess what else starts exactly at seven.” As quickly as his excitement detonated, it was collapsed. His demeanor completely reversed and he cleared his throat. It was a moment later that I realized that the waiter was returning with coffee and Johnny was only becoming protective of the information he was giving me.

Extending a waxen arm toward both of us, the waiter placed a cup of coffee next to our water. Fully extended, his limbs looked like paraffin taper candles. He glanced down at the menus which were still exactly where he left them, and the skin on his face melted into a somewhat disappointed expression. “Do you need more time?” I wasn’t sure if it was due to the man’s malnourished thinness, his cumbersome way of moving, or what, but it was like you could clearly see the various functions of his body taking place. You could see his stomach acid boiling, intestines curling and digesting the food he ate an hour ago, and the muscles in his neck contracting and relaxing as he turned his head and moved his mouth to speak. His eyes rolled in his skull to point at Johnny and back to me. Johnny told him that for now, we may just stick with coffee. The waiter told us to let him know if we needed anything else and scurried away, in the same manner that a opossum does when caught in headlights.

“Here’s the thing,” Johnny continued with anarchy gleaming in his eye, “all of the major news programs were there, in Libya, a country which takes several hours to reach by plane. Guess what time most news programs run their evening specials. Seven. And all of these news programs were in the right place, right on time. London, New York, Los Angeles, Paris- all the allies, they were all there. The bombing was timed for the news. Had to be. You know how big of a story that would be if we actually had a free press?” Johnny had a way of “seeing through” the various constructs of society and presenting them in a way which had you believing his conspiratorial rambling. “But there’s good ol’ Uncle Sam, telling you to sit and stay, teaching you to never look into these things. ‘Don’t go out and see the world, we are all the world you need.’ Look, if people won’t change it, you can’t change it. If you can’t change it, leave it.”

The next day, he started packing his bags.

From the sounds of hundreds of raindrops colliding with the aluminum roof of my car, I lost where I was for a second. For that second, I was back on a midnight beach on the east coast with Johnny. We were washing our hair in the waterfalls of the Rockies. We were back in the hills of Washington. That second of delusion was the best second I had in a long time. I gasped upon awakening. I had dreamt I was losing air under an avalanche of dirt. It was the tenth anniversary of Johnny’s great escape, the only one he never told me about. On this day, every year, I always take a “dark departure,” if only to remember how the act of leaving your own town feels, how it seems to just make your heart pump your blood around faster.

I saw that the moon’s spotlights were still beaming through the treeline, like the aura around a phantom, and I got out of the car- just a sprinkle now. I grabbed a flashlight and looked down at the torn tire and bent rim that the water had blessed me with. Out in the middle of nowhere, but I guess that was the best place to get stranded.

I had no phone- I had locked it in a drawer earlier that week in some sort of self-proclaimed rebellion against society’s various comforts. Being safe, always being seven buttons away from help. That was their thing, not mine. As the rebellion matured with the week, I got in my car and took the first dark road I could find out of town, fueled by Johnny’s energy. That was probably seven or eight hours ago. I didn’t know which direction I travelled, but I was out of the Midwest, I could tell. The air was easier to choke down. It didn’t seem to scratch at your esophagus, as if trying to claw its way back out. Why I stayed there so long, I don’t know.

Maybe I was in Arkansas. That would make sense. No, there were more hills than Arkansas had. Maybe I went West. Oh well. Where I was, irrelevant. I looked at my car- had the same one for a decade and a half now. The car. The car expanded the cities. Before the car, you could walk anywhere. Horses expanded the towns, cars made its radius a few days’ worth of hiking. Cars made small towns empires. My keys were still in the palm of my hand. I put them on the roof of my car. I took out my wallet- 152 dollars in varying amounts of society’s increments. Money. Money is society’s tool for support. Police enforce the rules of the system for paper the system told them was important. You can use it to put gas in your car, so you can drive to the other side of the city and back. It’s all a circle. I raised my hand to put the cash, credit cards, debit cards, checkbook, identification, insurance, business information and a bottle of prescription anti-depressants next to the keys.

It was that time of year when the dieback of winter began to hide behind green regrowth, and some of the flowers were starting a parade of resurrection down the sides of the road. “There’s just something about the first few days of Spring,” he used to say with a crooked smirk on half of his face, “after such a cold deadness, everything begins to live again, and you can feel that life starting.” A decade without you Johnny, and I walk in your image. This, I have perfected.

My head hurt. I didn’t remember hitting it on anything, but I took a glance at myself in the car mirror to check for bruises. I looked right into my eyes in a way I never had before. There were two separate people staring at each other- who I was and who I learned to be. Who I was and who they beat me into being. Who I was, and a reflection of them. They look in the mirror to pamper their faces, paint their skin into perfection. I saw both someone I recognized and someone I did not. I took off my rings and necklace, placed them on the roof of my car. Who I was, and Johnny.

My eyes got lost in the hills a half a day in the distance. Tranquility. It was nature’s darkness. I turned around and noticed the haze of a city over a nearby line of trees. Those were their lights. They make their own daytime so they never have to learn how to live in the night. They have learned safety. They have learned comfort. I put the flashlight next to the keys and wallet.

All my life, I had been waiting for an escape. An escape from society’s traps, a way to worm out of its tight boa-constrictor grasp. I looked at the city haze and pictured hundreds of people walking downtown, occupying bars and clubs, drinking their way into stupidity. I pictured children in school, learning to repress who they are, learning to always say the right things and to not cause trouble. You either repeat the official doctrine, or sound like a madman. “Your madmen today will be your prophets tomorrow,” Johnny would say. I remembered every cop that had ever pulled me over, telling me I was going too fast, too slow. Telling me I was too suspicious or too dirty. I was too threatening, too enclosed. I wasn’t perfectly conventional in some way or another. I pictured Johnny from grade school, and replayed memories of exploring the creeks in the backlands of subdivided Kentucky bluegrass and concrete. I thought of every friend I had, every enemy I had, every girl who had been tolerant enough to stick around long enough to break my heart. I thought of my mother, the way she would say “I love you” every time she left the room. I remember licking her spatulas, folding her towels for a quarter a basket. I remember her teaching me how to clean, how to maintain all of the things that put us under the ground. I thought of my father, the way those same words never escaped his dry lips. I thought of his loud, powerful voice reprimanding me for dropping grapefruit on the carpet. I remember the morals he tried to inject into my veins to replace my boiling blood. I remember how he taught me to be self-reliant, productive, useful. I thought of my siblings, perhaps the only real peers I will ever have. I remember the games we would play, the realities we would create.

I turned, and looked at the hills. I remember nothing. Somewhere beyond those hills, I knew, were mountains sleeping in their beds of eternity. I glanced at the things on the roof of my car. Those were important, but not to me. I grabbed my backpack, filled it with anything useful I found in that car. I always made sure to carry supplies, just in case an opportunity presented itself to me. I hooked my sleeping bag to it, and started walking toward the spine of the world. I didn’t even bother shutting my car doors. They hung open like the ribs of a meal left by a predator after it was finished. I could feel Johnny now, a poltergeist puppeteer pulling my arms and driving my steps.

Freedom. Each step was a step out of slavery, out of suppression, out of what I was taught to love but learned to hate. There is freedom in having nothing. There is freedom in having no one. Now I am free in ways nobody else is. And so the hills were my horizon, the mountains were my heaven to follow. Who am I? That is a tag. Where am I? Tag. I don’t know any of that anymore. I gave up those dog-collar facts. I don’t want to be returned if I am found. I am here, I am now. The moment you become lost, every direction becomes equal. Where you are and where you were going become the same. The sun was peeking around the corner, and the gears of the cosmos began a new day on the face of Earth’s clock. Behind the impulse was the hidden design to never turn back, and it was the moment to decide. A new day, a new place. A new place, a new life. Johnny is right next to me, with a smile that for once isn’t just a smirk. He is talking about destiny. My friend, my dear friend.

We are free.

Harley Ralph

Harley Ralph

Alec James

Harley Ralph always left work late. He had a deal worked out with his boss, in which he would come in at ten in the morning instead of nine, and leave at six in the evening instead of five. He told his boss that this is because he takes sleep aid medicine and he was concerned that his medically-induced weariness might result in occasional tardiness. The real reason is because he likes taking his time in the morning, and shifting the schedule by an hour allows him to miss both traffic climaxes in the day. He does not like driving in the heavy traffic rush- it irritates him easily. Since his work is typically immaculate, his boss usually doesn’t object to small requests like that, even though Harley believes him to be an absolute fool. On his first day twenty-two years, three months and a week ago, the moron insisted on calling him “Har-Har,” asking if that was okay. What self-disrespecting brainless fool would allow himself to accept such a ridiculous ridicule? But Harley said that it was fine with a plaster smile. Every time he comes in, he says “What’s happening, Har-Har?” and it fills Harley with so much frustration he just wants to yell and smash things into his skull, play around in the soup of his insides. But every day for twenty-two years, three months, and a week, he hasn’t.

Each day after he leaves work at six, Harley drives relatively undisturbed to a sandwich shop on Eve street, just a few blocks from his house where his wife tends to this or that on 267 Oak Street. There are thirty-two tables separated into three different sections. He always takes the table with the cushioned chair in the third section, furthest from the door in the back corner. The third section is comprised of smaller tables, so he can avoid the larger parties that just holler and make noise, distracting Harley. This table is typically open because when he arrives, usually between 6:13 and 6:17 in the evening, the masses of the idiots who go there after they get off work at five and who can’t figure out that everyone goes there when they get off work at five have mostly dissipated by then. However, if Harley’s table isn’t available, he sits at the table four down in the same row, in the south-facing chair so he is pointed at his table. As soon as it becomes available, he moves. He stays there usually until 7:13 to 7:17 in the evening, depending on when he first arrived. He does this every day of the week, except Fridays.

When he leaves Sal’s Sandwiches today, he will go home and meet his wife. She will greet him with exuberance, hugs, and kisses. She will tell him that she missed him all day, and she will tell him about how glad she is that he is home. She will ask Harley about his day, and Harley will insert a generic comment about the demand of his work, and how it is not fair of his boss to ask him to stay until seven at night every day. His wife will hug him and say “awe, I know honey. I’m sorry,” in the same way one’s dreadfully overwhelming aunt does to young pouting toddlers at family Christmases. Harley cringed.

In the morning, this woman will leave for work an hour and ten minutes before Harley does. The commute to her office nears twenty-five minutes while Harley’s averages about fifteen, and considering the fact that his wife works the conventional shift starting at 9:00 in the morning, that also gives Harley an hour and ten minutes in solitude. She will greet him in the morning in the same way she greets him in the evening, as if the eight hours they just spent sleeping not a foot away from each other was just as difficult to endure due to unconsciousness. She will ask how he slept, and he will say he slept fine having her next to him. Harley will then insert a generic statement about the dread he feels having to go into work. His wife will hug him and encourage him, telling him how she cannot even imagine how difficult ten-hour shifts can be all week. When she leaves, Harley will tend to his business, sometimes reading, sometimes crosswords, for an hour and ten minutes.

For the last twenty-two years, three months, and a week, he has gotten off work at seven and rushed home through the thirteen-to-seventeen-minute commute from his office on Washington Way to his home on 267 Oak Street to be greeted by his wife. He has kept his sandwich shop hour secret every single day for that stretch, every single day except one. Tomorrow will be the fifth anniversary of that day.

Four years, eleven months, three weeks, and six days ago, he was second in line at Sal’s Sandwiches waiting to order his six-inch herbed turkey sandwich with no onions and extra tomatoes with a cup of basil tomato soup on the side instead of the kettle cooked potato chips and a foam cup for decaffeinated coffee, which he refills twice. About thirteen years ago, he switched from the kettle cooked potato chips to the basil tomato soup because a sharp shard of potato chip somehow got caught in his gum, between one of his right canine and incisor teeth where it pestered him for nearly twenty-four hours before he finally managed to knock it loose with his tongue. He orders the foam disposable cup because he does not entirely trust the potentially subpar dishwashing methods of the staff’s machinery there. He was next in line to order this when he became aware of an awkward presence next to him, too close for him to feel comfortable with it persisting. Perhaps it was a space-occupying person attempting to analyze the menu, or maybe someone was scanning the tables for someone they were going to meet, too oblivious to acknowledge that he or she was certainly standing far too close to Harley. He turned slowly to make sense of the annoyance, and was met by his wife staring back into his eyes.

What? She’s here at Sal’s Sandwiches! This was undeniably a disaster. His secret was known. Never again would he be able to have the hour to himself, for now his wife would see through his scheme and realize that he actually leaves work at six! Perhaps he could at least cover his past tracks by saying that from this point on, he will be allowed to leave at six. But even if that approach worked, it would be met with exuberance from his wife. “That’s amazing,” she would say, “an extra hour we can have to ourselves!” This was horrible. Absolutely horrible.

Harley fixed his face immediately at the sight- if her presence was not welcomed with a warm smile, she would inquire far too thoroughly about her various curiosities concerning Harley’s internal thoughts. Sometimes even a smile was not enough. Her ability to sense any inauthenticity in the subtle features of one’s face was impeccable. The act of constructing genuinely happy and welcoming features using one’s brows, cheeks, and mouth became an instinctual practice. The entire face and body had to be theatricalized toward that aim. One had to completely abandon all internalized repulsions and actually believe that they did not exist, otherwise her insecurities would permit her to see through the dramatization. Even in times of surprise such as that instance, this reaction had to be practiced into instinct so it was allowed to occur in its final form within the split-second timeframe of a typical human being’s reaction, as to convince this woman that there were no conscious or subconscious repressions taking place behind the sheer physical engineering of facial musculature.

“Hello, Harley!” This woman was greeting him excitedly, speaking at a bothersome volume. Any layperson would not notice anything peculiar about this, however the absence of the standard embrace and kiss sequence told Harley that behind her burlesque falsifications of excitability, she was already suspicious of the fact that he was clearly at Sal’s Sandwiches, clearly at a time where he had been at work every day for over seventeen years prior. She was a lady of detail- her vast reservoirs of attention looked past not the slightest peculiarity, and as such there was exceptional danger in Harley’s position there, since the entire situation was grossly out of the ordinary. During times like these, keeping calm and preventing rushing thoughts was imperative.

By the time Harley greeted her back only a half-second later, initiating the hug and kiss sequence, limbs and facial expressions in place exactly where they needed to be, he already had his story figured out. This woman would alert him of the earliness of the time, and give him a curious look which she could not mask as is the case with genuine insecurity. He would then say that he was able to leave work early today due to pressing and atypical circumstances in his boss’ life. His wife called him, apparently, and his child has endured a terrible accident resulting in a broken arm! He had to leave the office early to meet his family at the hospital and due to his impending absence, relieved the rest of the workforce when he left, apologizing for the circumstances of course. He made the decision that since he was off so early, he thought he would stop by this curious sandwich shop and bring them both home a sandwich as so the chore of cooking dinner could be averted. He would say that he was glad she happened to wander in right at this moment, for she could now order exactly what she wanted, eliminating Harley’s guesswork and they could get out of the house instead of being cooped up in there like chickens. In the face of this kind act calling for genuine concern and thoughtfulness, her mind would replace her suspicion with the warmth and welcoming she desired. When he presented this story, her eyes relaxed their analyzing squint and gazed up at Harley with the glint of a grateful child, her head tilted to the side in acceptance with her mouth opening a bit as if to say how sweet he was for the thought. It worked- Harley’s improvisation was sufficient and better yet, he had secured his hour after work through her belief of it being a rarity.

Nonetheless, that day nearly five years ago was the day Harley realized that he must leave her.

Yes, it had gone too far that day. On Fridays, Harley’s wife attends an evening book club with other like-minded people to discuss their thoughts of what, in Harley’s mind, were literature’s newest dull dramas. They meet at a coffee house on the South side of town promptly at six, and leave promptly at eight-thirty in the evening. Initially, she had wanted Harley to join her, however both knew he would have to regretfully refrain from this empty interest of hers, since he works until seven. Since that day nearly five years ago, Harley has been frequenting various restaurants, motels, and pharmacies between the hours of 7:03 and 8:19 in the evening, the starting time depending fully on the placement of the specific establishment of that week, and how long it would conceivably take for Harley to traverse the roads from the office.

Every Friday since that day, perhaps one would find him at Antonio’s Italian Eatery at 7:09pm, attempting to complete two entrees by himself. Perhaps the next Friday, he could be seen swiftly leaving the Discount Motel at 7:24pm. Six minutes prior, he could be at the HealthMart down the road, purchasing contraception and tossing it in the trash on the way out. He was always back at 267 Oak street by 8:33pm, in time to greet his returning wife at the door with rehearsed love. He made sure to purchase all of this suspicious solitude using an extraneous checking account he opened strictly for this purpose, all clues of its existence being left in a manila folder in his top desk drawer at the office, which locks. It was taken out every Friday for use, and returned every Friday before 8:19pm. It sat in that drawer overnight, every night since his wife found him at Sal’s Sandwiches. Every night except tonight. Tonight the folder was in his suitcase. Harley glanced at his watch, which read 7:09pm. He started to chew a mint to mask the smell of coffee.

When he leaves Sal’s Sandwiches today, he will go home and meet his wife. She will greet him with exuberance, hugs, and kisses. She will tell him that she missed him all day, and she will tell him about how glad she is that he is home. She will ask Harley about his day, and Harley will insert a generic comment about the demand of his work, and how it is not fair of his boss to ask him to stay until seven at night every day. His wife will hug him and say “awe, I know honey. I’m sorry,” in the same way one’s dreadfully overwhelming aunt does to young pouting toddlers at family Christmases. Harley cringed.

In the morning, this woman will leave for work an hour and ten minutes before Harley does. The commute to her office nears twenty-five minutes while Harley’s averages at about fifteen, and considering the fact that his wife works the conventional shift starting at 9:00 in the morning, that also gives Harley an hour and ten minutes in solitude. She will greet him in the morning in the same way she greets him in the evening, as if the eight hours they just spent sleeping not a foot away from each other was just as difficult to endure due to unconsciousness. She will ask how he slept, and he will say he slept fine having her next to him. Harley will then insert a generic statement about the dread he feels having to go into work. His wife will hug him and encourage him, telling him how she cannot even imagine how difficult ten-hour shifts can be all week. When she leaves, Harley will tend to his business, sometimes reading, sometimes crosswords, for an hour and ten minutes.

However tomorrow morning, his business will be balancing his checkbook. When this woman leaves, Harley will neatly stack five years’ worth of bank statements, receipts, and transaction charts under the insufficient cover of a single book in the lower drawer of the living room desk and leave the door slightly cracked. Then as a garnish, Harley will leave a blue ballpoint pen on the surface of the desk. What a mistake! For a woman who picks up on every twitch of the eye, certainly this peculiarity would be plenty to stir her attention. She would arrive home at about 5:25 in the evening, notice the pen and the drawer askew, and investigate. She will find all of the papers and drag them out. When Harley arrives at 267 Oak Street, lain expanded across the entire surface of the desk will be undeniable proof of Harley’s infidelity. Dinners for two, swift visits to motels, family planning. Harley smiled.

Harley will finish all of his preparations for work around 9:40 in the morning. He will take one last look at his innocent crime, turn, pick up his suitcase, and drive to work relatively undisturbed.

Adrianne

Adrianne

Alec James

Hello Adrianne. I stood behind you in line at the grocery store one day, and I love you.

At first, it was just happenstance. In fact, the potency of my mental wanderings left me not even noticing you until after I was already directly there. But when I looked up, I saw you, and that was enough. I got the feeling that you were superimposed on the surface of the rest of the world, for against the relative flatness of everything else, you had such depth. I studied your long dark locks first, flowing down the outside of your skull like limber silk before surrendering into loose curls at your shoulder blades. Each curl’s edge was traced, as if by an artist, with glistening gold. My eyes fell on your left cheek next. It protruded forward, in a way which made it seem like your jowls were hugging your lips. Your skin was so pale, as if protected by some presence, looking powdered like a doll’s timeless fiberglass features. It was the first time I thought that skin, skin itself, could be intelligent. I traced the landscape of your facial profile. Your forehead curved out from your hairline, and I could see how it would form perfect circles had it been continued infinitely. However it fell into a basin under your brow, the skin then lifting in a gradual incline to form a small nose, with the nostrils expanding and contracting in occasional unfinished flares. I felt like a microbial mountaineer, ascending and descending the various peaks and valleys of a perfected paradise. Your mouth was brazenly outlined by soft cedar lips. The curve of your nose fell above them so sharply, that if I were to have leapt from its peak, I felt that I may have fallen straight through them. The contour of your lower lip, as it dipped and arched back out into your chin, formed the graceful strokes of a calligrapher. Your skin was so tight, rounding at the base of the jaw and pulling through the neck.

Your head turned at the base of the neck, perhaps 100 degrees, to focus on something to my back right, just long enough so that I could behold the balance of your face in its entirety. Something in your mind must have noticed me, because the nearness caused your pupils to contract and snap over to me. I could see entire worlds in there, an island of chromatic ridges in a sclera sea of perfect white. I could see blues, forming the skies and oceans, interknit with greens, forming land and life. Then at the center, the iris of the darkest imaginable black. An abysmal black that stretched on forever. When I was met with your iris, the universe began to play itself backwards. Stars expanded out into pink and green nebulae, solar systems and galaxies spun backwards into spheres of debris, and heavy elements split back into hydrogen. Finally, all of creation contracted into an infinite point smaller than any atom, and ceased into absolute silence. Nothing was left except that deep, illimitable black.

Each corner of your mouth stretched slightly into a small, hesitant smile before turning away, and life and light began again. I watched as the strands of your hair entwined together around your shoulders, some falling this way, others falling that. As it descended, it expanded in volume as the curls took over in the same manner that prairie eventually gives way to thick forest. It climbed down your upper back, following the bend. The hair began to wane only as your lower back began to protrude out again to form your backside, which was not fully allowed to finish before revealing itself, only slightly, from behind the frayed base of your shorts. Your wrists fell only slightly below, extended from thin, soft arms. Your left hand and fingers lightly gripped the mouth of a bottle with only enough force as to prevent it from slipping through your grasp. It was a large pink bottle, resembling that of an exotic perfume before that of an alcoholic beverage.

I have always found it curious, how in this world, your identity is so closely linked with various strands of numbers. Phones, identification, bank accounts, registration, license plates, addresses, age, and so on. At birth, we are rather given a strand of letters which perhaps we feel that our identity is connected to, enough to respond to it being called and recognize that this name we were given is applicable to our being. Perhaps we feel like this name is more closely linked to our identity than any of our descriptive numbers. Perhaps any given Christopher in the world feels as if he is more naturally “Christopher” rather than perhaps “431-2801.” However, numbers do a far more efficient job at distinguishing one particular person from the next. One human being may have hundreds of streams of numbers, all doubtlessly unique, extending from his or her life at any given moment. Any one of which can be followed back, like a trail of breadcrumbs, straight back to their doorstep. I suppose I am grateful for this nature, for without it, I may have never seen you again, Adrianne.

According to the last census, there are 177,272 people residing in Mallowsfield, and one of them is you.

31.87, 5:34:27, 11, 3397

After returning your identification, Adrianne, the cashier scanned your bottle and sent it down the line. I saw the numbers clearly on the screen, the numbers of fate, so conveniently pointed in our direction. A bottle of distilled spirits, just like the one you were holding, carries a tax rate of 6.25%. The bottle rang up at $29.99, with a total tax of $1.88, making your purchase $31.87. There was a digital clock in the upper right of the screen, dividing the current time up by the hour, minute and second. At the instant the receipt began printing out, the clock told me that the current time was 5:34 in the evening, with 27 seconds. Directly underneath the time and date lain the words “Lane 11” in red boldface.

You slipped the bottle in a slender paper bag and turned to leave. You did not look at me again as I hoped you would. Rather your eyes stood up to focus on the exit as you turned, your right arm tugging at the bag and raising the bottle to your chest in a clutch. Your left arm swung back and forth in the gravity. Your legs were clearly exposed, so I could see the muscles through your tight skin, as they contracted and relaxed, absorbing the shock of each step as your heels took turns impacting the speckled beige tile. I watched the various components of your body work to propel you against friction and gravity until you had turned the corner and vanished, like an apparition or hallucination.

I returned to the store after bringing my groceries to my vehicle in the lot. I went up to customer service, and faced the associate. She was an older lady with a friendly face, short brown hair with highlights, and sunspots on her leathered skin. She thanked the man ahead of me with a smile as he left, and raised her brow as she faced her widened eyes toward me and lifted her chin, inviting me to the desk. She asked how she could help me, and I said I misplaced my receipt. I was in line just a few minutes ago, and have no idea what I could have done with it. I wondered aloud to her if there was any way that a secondary copy could be printed off. She said of course with a seemingly genuine excitability. When she asked for further details, I responded that I remembered the approximate time, amount, and terminal that I checked out at. It was that easy, and I attained a concrete artifact of our first meeting, Adrianne. In my hands, I held a fossil of your existence at a certain point in space at a certain point in time. Underneath the total, the receipt held the fact that you paid with a Visa card, with the last four digits being 3397. Yet below that, the words “Thank you, Adrianne W” met my eyes.

That is how I learned your name, Adrianne.

742-1408

I must admit, I did not spend any time on social media before I met you, Adrianne. It was a bit out of my time, I’m afraid. However, I know that you younger people take part. In this age, I figured it would be far easier to find you using Facebook rather than searching through public records and the like. I was right.

I made a new email account and falsified a name, and just like that, I had access to probably 75% of the city of Mallowsfield. This town has 177,272 people in it, and with a name like “Adrianne,” it narrows it down quite drastically. There were only three listed by the time I finished your first name in the search bar, each with a headshot of the individual. This town has 177,272 people in it, and only one is named Adrianne Wilkinson. I hovered my cursor over your face for a while, tracing your jawline, stroking your brow. The dark hair framed your alabaster skin, making your piercing blue-green eyes all the more pungent. I combed my fingers through your hair with the mouse a few times, imagining how soft it must be on the webbing of my fingers. I tucked your bangs around the rim of your ear and fit them into the back groove where the ear meets the skull, continuing down to your neck before the picture cut off, and clicked. It seems I got excited prematurely, for very little was visible on your page. I attained a larger version of your profile picture, however it seems that most any content beyond that was hidden. I found out later that there are extensive privacy settings trying to separate us, Adrianne.

It took me a few tries before I got to Hannah Perry. She worked as a waitress at a diner called The Wallflower on Willow road, the commercial side of town. One thing I was able to salvage from your online presence was a handful of names on your friends list each time I refreshed the page. Not all of them were hidden, and many of them had their place of employment listed for any member of the public to see. I went to The Wallflower on a Saturday evening for dinner and managed to glance at the blueprint of the establishment laying on the hostess podium. “Hannah” was scribbled in light green dry-erase letters in section B2, along the East windows. The hostess was a younger girl, skinny, with a tattoo of vining roses crawling around her shoulder. I asked her if I could please have a booth next to the windows, extending my pointer finger toward section B2, and there she sat me.

I recognized Hannah immediately from the pictures. She had bright blonde hair, perfectly straight, and pulled back into a ponytail. She was tending to another table in B2 when she noticed that I was sat. She reappeared from behind the kitchen with a few glasses on a tray balanced in her palm. She placed them down at the other table and scurried over to greet me.

“I’m so sorry if you were waiting long!” She rummaged through her apron to extract a small black book to take down notes. I could clearly see her face now. It was almost dirt brown, due perhaps to a combination of tanning and foundation, which was applied so thickly across her face that I felt like I could chip it off in chunks with my fingernails. Her head was long and narrow, stretching down into a thin chin before diving into a black button-down blouse. Her eyes rose back to me, a bright brown met mine.

I formed a welcoming smile. “No, don’t worry. I just got here.” I nodded my head and pushed my face into an even larger smile.

“Oh good! Welcome to The Wallflower, my name is Hannah and I will be taking care of you this evening. Could I get you started with something to drink?” She welcomed me in with a genuine smile.

I turned my head back to the menu and ordered a cup of decaf and a plain cheeseburger. “Oh, and you said it was Hannah, right?” She nodded at me with an attentive smile. “I was planning on being here a while, that won’t stop you from being able to go home or anything would it?”

“Oh, not at all! We close at nine and I have the late shift, so you have until then. Take your time! Your order should be right out.” She hurriedly walked away to tend to other tables, and I pulled out that day’s newspaper.

Just before nine, I thanked Hannah, complimented her service excitedly and tipped her $10 on a $14 ticket in hopes of creating some feeling of obligation in the event I am faced with an unfortunate circumstance later in the evening. Through the diner’s windows, I watched her complete her closing work. I braced my car’s hood open, and waited.

She walked through the doors about twenty minutes later with another coworker.

“Hannah?” I called her name, and her head turned to face me as her steps grew slower. The two waitresses made their way over to me.

I told her that my car wouldn’t seem to start, and I feel badly for bothering her. I introduced myself to both of them as Mark, and thanked them for hearing me out.

“I was just wondering if you had a cell phone I could use to call my son, just real quick?” I made sure to appear upset and breathe heavily. Hannah shuffled through her pockets and handed me a thin, white phone with a pink jeweled case wrapping the sides and back.

“Oh, thank you so much, you are so sweet. I’ll have to call your boss in the morning and tell him how great you are. I’m so sorry.” She smiled and said she was glad to help. I focused quickly on the device, and tapped the button that said “contacts.” It helps that your name falls so high in the alphabet, Adrianne, for I found you, clicked on you, and committed your phone number to memory before more than a few seconds went by. I closed out of everything to return to the home screen. 742-1408. 742-1408.

“I’m so sorry, girls. I have one of those older phones, I have no idea how to work this. How do you dial?”

They giggled at each other and were eager to help an older man figure out the new world’s baffling technology, dialing a dead phone number at my instruction. I feigned a conversation relaying my situation to my imaginary son, and let the girls know that he was on his way, and thanked them for all of their help. They smiled and left. You have such nice friends, Adrianne. 742-1408. 742-1408.

2820 Mallard Way, Mallowsfield, NE 69811

Every housed person in the country has most, if not all, of the following things: utilities, phone service, DMV records, bank and credit history, perhaps television and internet services, and so on. All of these venues have valuable information, and friendly customer service associates willing to help distressed customers. There are only so many cellular service providers, Adrianne. Although I do hate guesswork, this was little more than simple mathematics. I began by calling the one with the largest customer base. I was at the grocery store where we first met, Adrianne, and the kind lady behind the customer service desk let me use the store phone to call for a taxi. Pressing this or that key when prompted, I eventually broke through to a human customer service representative, citing issues with my phone. The lady on the other end asked me to name off my phone number to pull up the account. 742-1408. 742-1408.

“Uh, you’re Adrianne?” the voice said with a curious suspicion.

“Well, I’m Adrian Wilkinson.”

“Oh!” The voice giggled in embarrassment. “I’m sorry sir! You are having an issue with your phone?”

I chuckled back and assured her it was an inconsequential mistake. I apologized if she was hearing any background noise, I was calling from my work phone and people seemed to be particularly noisy today. If it were the case that she had caller ID, that would explain why the displayed number was not 742-1408. If I were to make any mistakes in the future, even if they have the capabilities of reverse lookup, they would get the Neighborhood Food Market in the middle of Nebraska. “Well, I haven’t gotten my bill yet. Usually it would have been here a week or so ago. I was wondering what I owe on my account?”

“Of course, sir. Can you verify the last four digits of the card on the account?”

“Is it the Visa?”

“Yes sir.”

“3397.”

“We are showing that you owe the typical $90 for the month of April Mr. Wilkinson, no extraneous charges.”

“Oh excellent,” I said with a relief. “You have the right address on file right? I didn’t get the bill.”

“We have 2820 Mallard Way, Mallowsfield, Nebraska 69811.”

V43 578

Your mother has your hair, Adrianne. There are 177,272 people residing in Mallowsfield, and one of them is you.

There are digital maps everywhere, containing every street, road, and trail in the country. It is not difficult to find any given address anymore. There are so many services and technologies making modern life so much easier. I made my way to the west side of town, where Mallard Way stretches through about a half mile. They were nice houses under an umbrella of thriving canopies, with a well-known city park on one side. The unique four-digit numbers being repeatedly printed blatantly on the curb, mailboxes, and houses themselves were only a convenience at this point. I passed 2820 a couple times. It was too far separated from the park for that alibi to shroud me. However, I parked down the street and waited for two hours, with the excuse ready that I was simply lost had anyone shot me suspicious looks.

Two hours after I arrived, a newer SUV pulled into the driveway and came to a halt halfway up. An older man stepped from the vehicle. He was perhaps only a few years younger than me, placing him in his mid-forties. He had thick straight salt-and-pepper hair combed over to the left which bounced slightly as he stepped down the driveway toward the curb. He was wearing a light blue polo with a perfectly folded collar and light tan khaki pants, just short enough to allow me to see brown striped socks from underneath the hem whenever he bent slightly at the knee. Wrapping around his heel were a pair of dark brown tassel loafers which folded at the base of the metatarsals each time he extended the other foot for a step. He walked with confidence as he rounded to pop the door off of the mouth of the mailbox. He closed it and, shuffling through letters and junk mail, walked back up to the open door of the SUV and pulled it into the garage.

Only a few minutes later, a silver Volvo four-door pushed passed my car. It caught my attention and I watched as it rolled down another half-block to 2820. A middle-aged woman who was walking in the opposite direction stretched her cheeks into a child-like smile at the sight and waved ecstatically at the Volvo before it turned to climb the driveway’s incline and disappeared into the garage. A woman walked out of the garage, dark flowing hair which waved down her back. She turned her head and waved at the woman who was walking down the sidewalk. Adrianne, she had your thin arms. The two women met at the base of the driveway and conversed for a few minutes before separating. When they did, the walking woman continued in the direction she started and the other woman, walking with the same conviction that you do, returned to the house through the garage.

Obviously, I was looking at your parents’ house. After I watched for a few days consecutively, it also became clear that you did not live there. However, through the mail I did learn your parents’ names, and which insurance companies, utility providers, and cable services they probably used.

On the third day, I arrived earlier. That was the day that I realized you had a younger sister. There has been a car parked along the curb across the street from 2820 every night that I have watched. However, only when I arrived just before three in the afternoon did I actually see who owned that vehicle. In all honesty, there were cars all up and down that street parked on the side of the road- I hardly paid it any mind at first. It was an older dark red Volkswagen hatchback, maybe nine or ten years old. I hadn’t even realized it was missing that day until it pulled up into the exact spot it had occupied throughout the week. I watched as an adolescent girl exited and crossed the street toward your parents’ house. I began to focus intently as she walked up the driveway, and entered a code into the side panel, opening the garage door. She also had dark hair which rolled down her back, and the trademark Wilkinson thin arms. About a minute later, the lights in one of the upstairs windows flickered on. Unfortunately, I could not see anything other than the occasional shadow through the window due to the blinds remaining closed. But due to the length of time the room seemed to be occupied in the absence of anyone else, I concluded that it must be her room. I looked back at the Volkswagen and took note of the license plate number, which was V43 578.

There were plenty of other safer, less direct ways to find you, Adrianne. For example, any given city only has a handful of utility providers. Usually even fewer than they do cell phone carriers. Unless you have solar panels or a wind farm, your power comes from one of them. Better yet, most utility companies have implemented automated synthetic voices for their customer service line. Do you know how they organize their accounts Adrianne? By phone number. The voice tells me to enter your phone number using the keypad, and sometimes they even verify the account by reading back the associated name and address to the caller, all before I even have to talk to a real person. You can get away with listing your parents’ address with cell phone companies, store rewards cards, and even official documentation like driver’s licenses. But since it was coming directly from the utility company you set up your services with, it would be your real address no question. You had to use your current address, or they wouldn’t know where to provide services to.

I could have done something like that. But I decided that your sister could lead me to you more naturally.

04/14/1990, R23 990.

Throughout the next week, I learned things about your sister. She leaves the house around 7:50 in the morning to go to Mallowsfield High School, usually arriving at least a few minutes late. Monday through Friday, she gets out of school at three in the afternoon and usually goes home afterwards. Two or three times a week, she goes to a coffee shop or café with a friend. She works after school on Fridays and throughout the weekend at varying times at the mall on the West side of town. She is a checker at a clothing store called Maxwell’s. I found her name was Aubrey (Wilkinson I assume, as your biological parents seem to be together and that is the last name associated with every piece of mail arriving at the house) by glancing at her nametag when I went in there to look at socks when she was working.

However one day, I saw her in a supermarket purchasing a birthday card. I was very pleased when I found that it came from the “Sister” section. I grabbed a copy of the same card and got behind her in line.

“Hey, isn’t that something!” She turned quickly to face me, and followed my face from bottom to top a couple of times with her bright eyes, similar to yours. I held out the card with a smile, and pointed at her hand.

She glanced at my card, glanced at the one in her hand, and dropped her shoulders with a smile. “Oh,” she managed to let out with a larger exhale than was necessary for the word, almost in relief to have gotten an explanation for my confrontation of her.

I laughed it off. “I bet my sister is older than yours though! Are you the older sister or the younger sister?”

“Oh no, she’s older than me. She turns 22 next Wednesday.” She had such a young smile.

“Aren’t you a great sister to be getting her that! Are you planning anything big for her?”

“No, nothing big, we’re just going to hang out with her a little bit just like we do every year.”

“Well you tell her that she has a sweet little sister!” I smiled at her and she smiled back. The cashier scanned it through and gave her the total. She pulled a few dollars out of her back pocket and left the store, looking back at me with a shy wave on her way out. When it was my turn, I told the cashier I accidently forgot something, and that I would be right back. I left the store.

I left your parents’ house alone for nearly a week, until the next Wednesday. April 14th, 2012 is the next time I saw you, Adrianne. You were just as gorgeous, if not more so, as day one. It was not long before you arrived at the house. You drive a deep blue Ford four-door, perhaps of the year 2006, 2007, something around there. I drove directly by your house to get more details. License plate number R23 990. I kept driving in the direction you came from and parked at the edge of a road perpendicular to Mallard Way, but where I could still easily see your car parked. You came from the East, so once you leave, you will go back East. I waited.

Butler Apartment Complex, 3C, 435 Park Drive.

The rest is not important. In a nutshell, I followed you home. I kept my distance. If you were in the left lane, I stayed in the right lane. When we got to residential streets, I turned only just in time to see your taillights vanishing around the next corner. When you pulled into Butler Apartments, I would pull into a driveway across the street and watch you walk into the door labeled “3C.” I would call the apartment complex posing as an interested client, getting the name of the landlord so I could call back. I would ask the landlord to see a unit, which he was more than happy to oblige to. I would ask general questions about the complex, and learn that 3C is one of the small, one-bedroom units, eliminating most of the possibility of roommates. Pets, such as a loyal dog with a strong bite, were strictly not allowed. I would learn intimately the layout of your apartment during this session by asking to see a one-bedroom unit next. I would find your workplace and frequented businesses. I would be able to construct, with minimal error, your weekly schedule. Soon after, I would be able to finalize my plans to finally talk to you. I would later call you posing as your landlord, letting you know that there is someone coming to redo the caulking in the bathroom. You would open the door for me when I arrived right on time with a tool bag. There are 177,272 people residing in Mallowsfield, and one of them is you. This is how I have found you, Adrianne. The rest is not important. What matters now is that when I close the door behind me, I can turn to you, look you directly in your gorgeous blue-green eyes for the second time, and say:

“Hello Adrianne. I stood behind you in line at the grocery store one day, and I love you.”